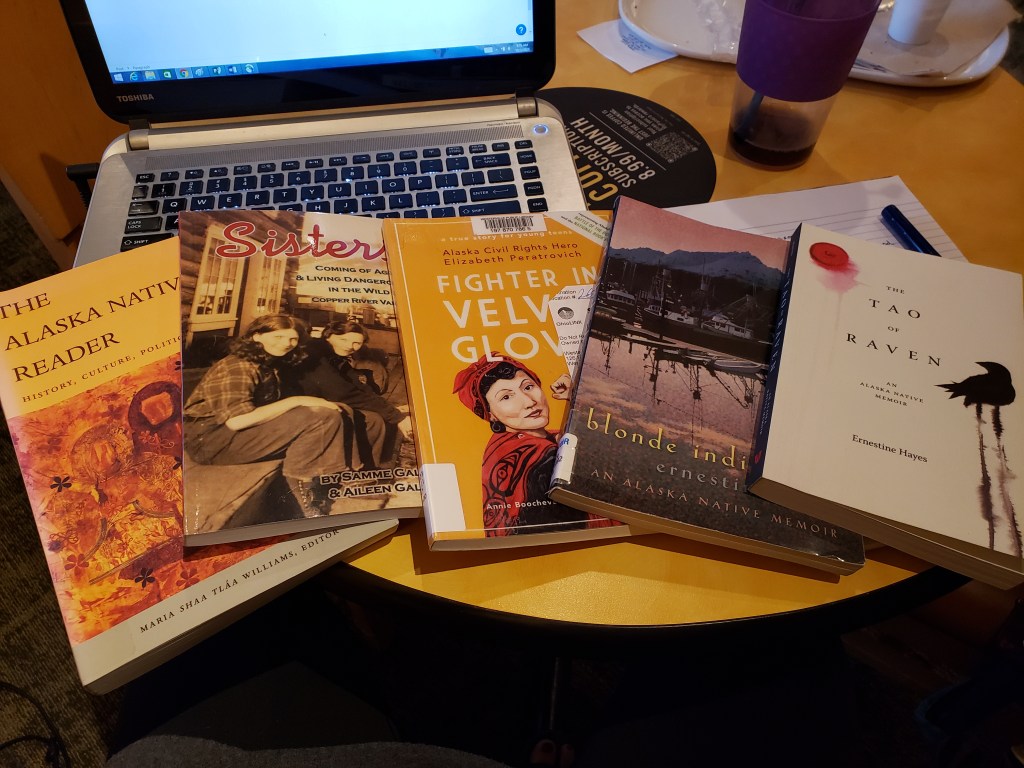

My OhioLink books arrived this past week! Now in addition to my writing I have some serious reading to get done. The first book I read was The Alaska Flying Expedition by Stan Cohen. It provided me with a time-line for my story since it begins with the announcement of the expedition and ends when the planes arrive in Nome. The second book I read was Sisters by Samme and Aileen Gallaher, an autobiography of two young women moving to Alaska in 1925. But soon after reading it I realized that it was the overly glorified white perspective. The Gallaher sisters were people who I could easily relate to, and could be similar to my main character, Margaret, but it was romanticizing and white-washing Alaska.

So allow me to introduce to you the line-up designed to start my education on Native Alaskans. I’m starting with The Alaska Native Reader, an anthology of oral traditions, scholarly articles, memories, poems, and art. I’m about 50 pages in, and already their cultures have become more dimensional to me compared to the flat version our modern society entraps them in.

Next up will be Blond Indian and The Tao of Raven, both by Ernestine Hayes. I anticipate a struggle reading those because her style is very… literary. I prefer a direct style with limited airy metaphors. It sounds beautiful, but becomes dense and difficult to sort through. Perhaps I’m just being lazy, but when reading to learn, to research, I don’t want to read a paragraph 2-3 times to work out an author’s meaning. But I will read them both because they are well known Alaska Native memoirs.

The final book in my pile is Fighter in Velvet Gloves, the story of Elizabeth Peratrovich, an Alaskan civil rights leader. It’s not set in the 1920s, but I hope it will give me a better understanding of the challenges of living in a Jim Crow Alaska.

Before I started to research Alaska, I didn’t have any strong sense of what an Alaskan Native was. We didn’t study them in 12 years of public school, no mention of them in 4 years of private liberal arts education, or graduate school. I just had what mother culture implicitly taught, which could be reduced to: Eskimos, cold, hardship, hunter-gatherers, White Fang, Balto, and Europeans bringing modernization.

The first lesson The Alaska Native Reader has taught me is that Native Alaskans, in all their diversity, were not the hunter gatherers that outsiders labeled them. They did not focus only surviving today, but planned for the long term health of their community. They prepared for future seasons, for subsistence harvest, for moving camps, and threats.

As an example of long term planning, take caribou fences. They were shaped like a funnel with a wide mouth. Caribou were driven into them where they were snared and killed. Seems simple, right? But the logistics going into it are massive.

First, it took quite a few years to learn the most common caribou migration paths so that a good site could be selected. During the construction they needed to figure out the orientation, have enough labor to build it, find the materials (which were usually not near the site), transport the materials, and the time to construct it. To understand how large of an undertaking this was, you need to know that these fences were up to 10 miles long. 10 miles worth of wooden posts, sinew for tying them together. 10 miles of people stretched out to herd the caribou into the funnel. The initial building was huge, the operation was demanding, and the yearly maintenance.

Caribou fences were not an endeavor of a “simple” hunter-gatherer society living day-to-day. It was elaborate and intensive, requiring a lot of planning and coordinating. Building a caribou seems to be is at least on par with the Serpent Mound, just less permanent, so more difficult to appreciate.

I’m aware that what I am just now learning is likely common knowledge to Alaskans, but I hope the enthusiasm with which I am learning now at least partially makes up for it’s lateness.